In 1918, a young pharmacy apprentice and entrepreneur named Jacob Sogboyega Odulate, popularly known as “The Blessed Jacob,” formulated what would become one of Africa’s most enduring pharmaceutical products: Alabukun Powder.

The name “Alabukun,” which means “The Blessed One” in Yoruba, was fitting for a product that would go on to outlive its creator and embed itself in the fabric of Nigerian life.

Written by Titilayo Oladapo-Ariyo | Edited by Jide Awulonu

Over 100 years later, Alabukun is still sold in roadside stalls, open markets, and pharmacies across Nigeria and West Africa, with its reach extending as far as Europe, North America, and even China. It holds the distinction of being the longest-running indigenous pharmaceutical brand in Africa.

But how did a simple powder created in Abeokuta by a largely self-taught young man achieve this kind of longevity in a country where countless local products fade away in less than a decade?

When Jacob Odulate introduced Alabukun, the modern pharmaceutical industry in Nigeria was virtually non-existent. Western medicines were rare, expensive, and controlled by European importers.

Meanwhile, in the United States, aspirin-caffeine powders were just becoming popular. Odulate spotted a gap: Nigerians needed a medicine that was accessible, effective, and trusted.

Alabukun entered the scene as the right solution at the right time.

Odulate didn’t just copy Western formulas; he innovated by blending imported patent drugs with local knowledge of traditional medicine. The powder combined aspirin (for pain relief and inflammation) and caffeine (for alertness and circulation), creating a versatile remedy that could address multiple ailments. This fusion gave Alabukun both the credibility of “white man’s medicine” and the familiarity of local remedies.

Accessibility was one of Odulate’s greatest strengths. From his very first stall in Abeokuta, Alabukun was positioned close to the people, unlike European medicines that were confined to elite hospitals or colonial trading posts. He also pioneered the small, affordable packaging. A single sachet that even the average trader or farmer could afford. Over a century later, this pricing strategy still keeps Alabukun within reach: a pack of 10 sachets today sells for about 200 naira (46 cents).

Unlike tablets, Alabukun’s powder form dissolves quickly, providing faster relief.

More importantly, it became known as a gbogbonise, a Yoruba word meaning “a cure for everything.”

Nigerians didn’t need to buy different medicines for fever, headache, back pain, or toothache. With one powder, they felt covered. The powder could be mixed with water or palm oil and was trusted to treat fatigue, migraines, rheumatic pain, and even serve as a blood thinner to prevent clots.

Its versatility made it a household essential, passed down from one generation to the next.

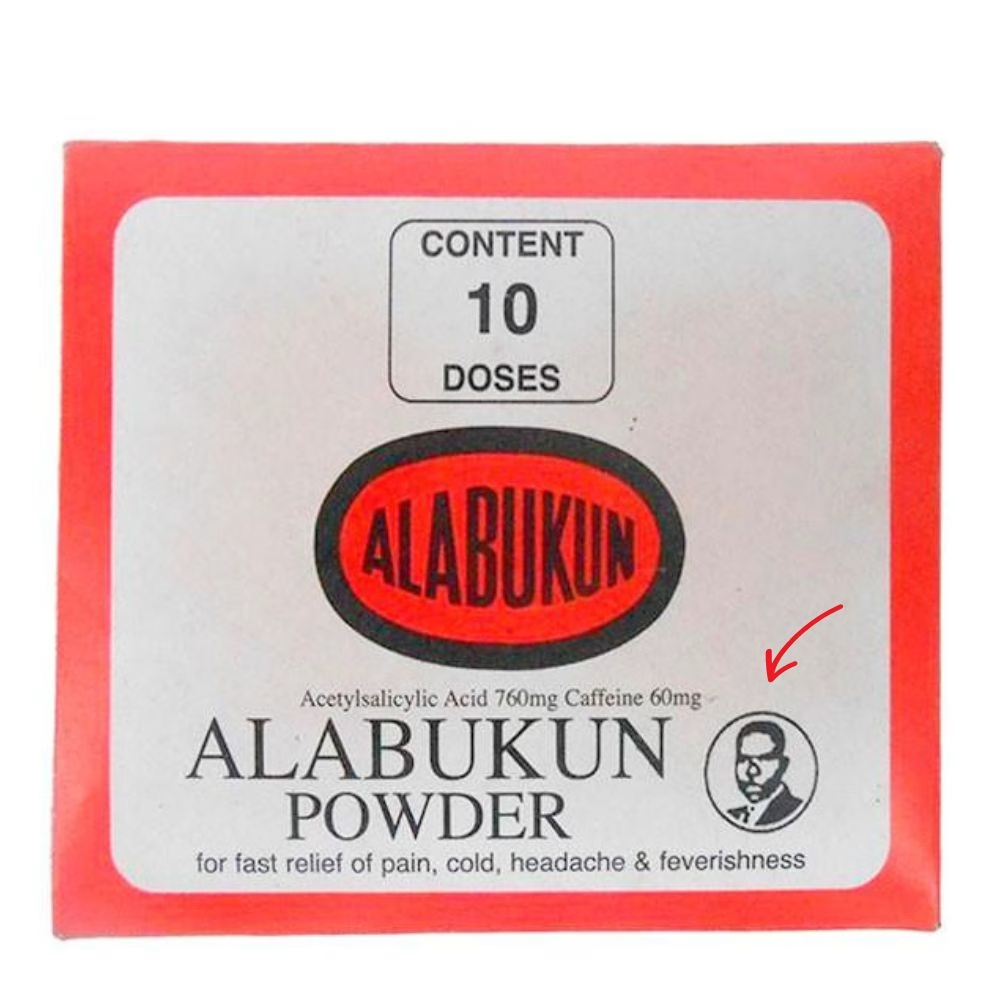

Odulate was already a respected medicine man in Abeokuta, and he leveraged that reputation to build confidence in Alabukun. By adding his own picture to the packaging, a bold move for the era, he gave the product a personal guarantee.

This authenticity, combined with real results, allowed Alabukun to spread through the most powerful marketing tool available: word of mouth.

While Alabukun Powder became his flagship product, Odulate also produced Alabukun Menthol and the famous Alabukun Almanac, which was distributed across Nigeria. The almanac, in particular, kept the name “Alabukun” alive in homes year after year, even among people who may not have used the medicine regularly.

Jacob Odulate died in 1962, but his story is one of quiet genius and enduring legacy. With little more than intuition, grit, and an understanding of his people’s needs, he built a product that has outlived him by more than six decades and continues to serve millions across the world.

Alabukun is not just a powder, it is a symbol of that businesses can survive in Nigeria. It reminds us that ingenuity and resilience can trump economic recessions, hardships and difficulties that come with running a successful business in Nigeria.

Even Nobel Laureate Wole Soyinka, in his memoir Ake: The Years of Childhood (which we had the honour of redesigning – see here), recalls Alabukun as a fixture of everyday life, cementing its place not only in Nigerian medicine but also in the country’s cultural memory.

To this day, every sachet of Alabukun carries Jacob’s vision forward: simple, trusted, and truly blessed.

At Toast Creative Studios, we design and nurture brands that don’t just survive in Nigeria’s tough market but grow, adapt, and thrive for generations.